By

DR Niall Campbell BDS MFDS Dip Clin Hyp PG Dip Psych

Communications manager DARA Thailand

SWIMMING BLIND

Two young fish are swimming along in the sea, minding their own business

An older fish swims by them and says – ‘morning boys – how’s the water? ‘

A few yards past one of the younger fish turns to the other, bemused, and says,

What the hell is water?

We are all surrounded by something as total and ‘all encompassing’ as water is to a fish in the sea. We are surrounded by an entity so complete it is as if it is hiding in plain sight. We live it, we breathe it, and we rarely notice it – because It is all we know. It is our ‘medium’.

It is our cultures.

Now you might think there is a very obvious grammatical mistake in the previous sentence. Surely it should say, ‘It is our culture’.

But the truth is that there are countless numbers of cultures across the world. Whilst this great variety of cultures undoubtedly contributes to kaleidoscopic richness of our planet, they all have their roots in tribalism, and they can therefore also propagate the unsavoury ‘them and us’ mentality.

More specifically for people with issues related to addiction,

This world of contrasting cultures can also act as a significant barrier on the path to enduring recovery. Before I explain why this is the case, we need to look back at the history of our species, and how our brains developed as we evolved from cave men and women, to the sophisticated, smart phone using, latte drinking creatures of the 21st century!

HARDWIRED FOR TRIBALISM

There are countless cultures, and each one has been constantly refined and differentiated (often in relative isolation from other cultures) over more than 125,000 or so human generations. Until the modern era of telecommunications and mass transit, humans therefore tended to be born, to live and to die, amongst a very small group of people (who were very similar to themselves in appearance ethnicity, behaviours, lifestyle etc.). Furthermore, when we swapped our nomadic hunter gatherer ways in favour of basic agriculture we started to ‘stay put’. We realised it was easier to pen all our animals in to a field and then just hit them over the head with a club when we got hungry, instead of having to actually hunt them down over hundreds of miles in the wild. We stopped roaming from place to place, and different tribes and collectives of people started to identify very strongly with where they were ‘from’.

These two things, – exclusively socialising with a small group of people, and becoming tied to a certain part of the world, meant that the ‘human way of life’ became to;

‘See the same faces, and live in the same places’.

This social and geographical stasis was the crucible in which disparate cultures started to form. It was also a time when our brains started to really ‘gear up’. We exponentially developed language and an ever-increasing ability to co-operate. Our big juicy modern brains (refined for socialising in tight knit groups) really started to evolve.

We became hardwired to know that, if we wanted to survive,

we had better learn to fit in with the group we have been born into.

MODERN EXCLUSION, ANCIENT PAIN

So as you can see, our brains are therefore predicated on a need to belong to a group. From an evolutionary perspective, this was an obvious survival necessity. If you were ostracised from the tribe, you were banished, and this meant death. Out in the wilderness all on your lonesome, you were easy pickings for predators (if starvation didn’t get you first). The following equation therefore became deeply encoded in our Neolithic brains:

Social death = real death

Now of course, in a societal sense, things have moved on. It is perfectly feasible to keep to yourself, to forego social contact with others, to think differently and independently and not get eaten by a sabre tooth tiger.

But the more primitive parts of our brains missed that particular memo.

This caveman and cavewoman part of the brain still thinks there is a significant ‘existential risk’ from exclusion. It hasn’t really caught up with our modern world.

And so these primitive parts of our brains get very antsy when we do things that constitute a break away from the communities and the cultures that we find ourselves a part of. If we are ostracised, even in our modern world, these primitive parts of our brain ‘fire’.

They neurologically scold us because they think that such rash actions may cause us to risk our very survival.

They cause pain.

Exclusion hurts.

Think about it. Lets say you go to have a good old Facebook stalk of someone you used to know; maybe an ex partner or a schoolmate, maybe a colleague who has just popped into your head. You type their name into the search bar and,Nothing.

Nothing.

They have unfriended you.

Ouch.

You haven’t given them so much as a second thought in over a decade. You might not even have been that close at the time. It was all but a fleeting curiosity that made you even bother to check in on them in the first place. You are not a part of their life and they are not a part of yours.

But still.

Ouch.

Being socially excluded – even from banal and inconsequential relationships –hurts. That is not a metaphysical claim, it is a scientific one. New research is showing all the time that the links between social isolation and our core physiology are perhaps more profound than we previously imagined. 1 2

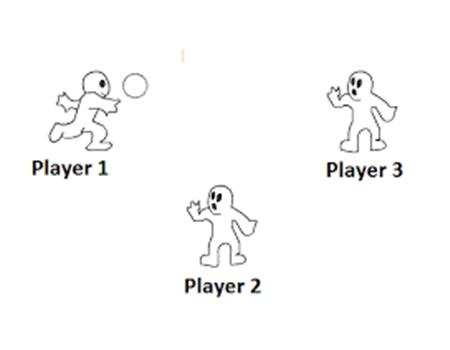

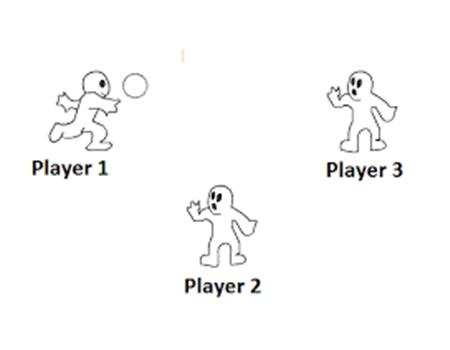

Researchers at the University of California invited people to join in with a little virtual ‘ball toss’ game called ‘cyber ball’. It’s a super basic game that looks like this:

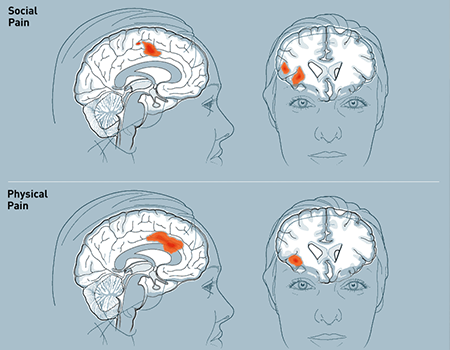

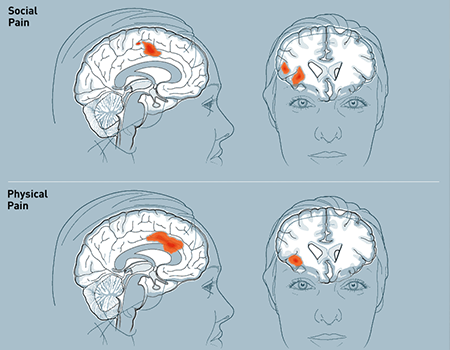

They got participants to lie in an fMRI machine whilst they played cyber ball. This is a piece of equipment that tracks blood flow to different parts of the brain. It looks like this.

MRI machines can show in ‘real time’ what parts of the brain are active under different circumstances.

So the researchers had participants play the little ball toss game, but the participants didn’t really know why they were being asked to play. Scientists can be sneaky like that. So anyway, the little ball is being tossed around fairly evenly between all the players, but then, for no apparent reason, the participants little avatar doesn’t get the ball passed to it anymore. It gets left out of the little game. This is of course the true purpose of the experiment. The researchers wanted to see, ‘real; time’ what the participants brain response would be to this inexplicable rejection from the group.

The researchers then noted that the same parts of the brain that ‘light up’ on the fMRI in response to physical pain, started to light up in response to this trivial little social exclusion from a ball toss game.

Source Lieberman, M. D., Jarcho, J. M., Berman, S., Naliboff, B. D., Suyenobu, B. Y., Mandelkern, M., & Mayer, E. A. (2004). The neural correlates of placebo effects: a disruption account. Neuroimage, 22(1), 447-455.

Illustration – Samuel valasco 3

The same components and pathways of the brain that mediate response to physical pain are also implicated in the response to social exclusion.

This is why if you get rejected by a lover it can feel as if you have been shot, this is why being unfriended by a random acquaintance on Facebook can make you feel lousy all day, and this is why breaking away from a culture which contributed to your addiction (maybe a culture of workaholism in your company, a national culture of drinking, or a culture of drug taking in your music or arts scene) can be such a daunting thing.

You are afraid of being rejected and forgotten about by a group that you were previously a part of, because you know that it will HURT.

- Socially,

- Emotionally, and as it turns out,

- Physically

The truth about culture is that you can never really escape it, unless you choose to live in a cave. So what do we do? My suggestion is that you create a culture of YOU, and in part two of this blog I will outline not only more about how culture has perhaps shaped your addiction, but also how you can engineer a life of positive change. A life where you stand on your own two feet, a life that embodies the concept of interdependence – not being a depedant sheep, but not being an independent lone wolf either.

The key to achieving this is getting your new ‘personal culture’ to line up with your core personal values.

It might be hard in the beginning to shake things up so that you feel no dissonance between your behaviours and who you really are as a person, but once you become more independent in terms of the way you think about your social and cultural connections, the world really is your oyster.

You can pick and choose what you like about different ways of life, and leave the other components (that don’t resonate with the most authentic version of you), on the shelf.

Will there be some pain to begin with? Sure! But when it comes to making the culture of YOU, it’s a case of a little bit of pain to begin with, but then massive gain on the other side.

Why live in a ‘one size fits all’ cultural suit, when you can tailor make your own?

References

1 Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290-292.

2 MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2005). Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological bulletin, 131(2), 202.

3 Lieberman, M. D., Jarcho, J. M., Berman, S., Naliboff, B. D., Suyenobu, B. Y., Mandelkern, M., & Mayer, E. A. (2004). The neural correlates of placebo effects: a disruption account. Neuroimage, 22(1), 447-455.